Seven days in the week. Seven deadly sins. Seven million people die every year from air pollution. That’s more than the number of deaths from malaria, AIDS and TB combined. Seven, a lucky number?

Air pollution causes and aggravates respiratory conditions such as asthma, emphysema and bronchiectasis. It also affects chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, cardiovascular disease including heart attacks and stroke, and can cause developmental problems of the lungs of infants, making them more vulnerable to these conditions in adulthood.

Oct 29-Nov 1 Unmask My City (UMC) – a global network of health practitioners championing clean, safe air in our cities, was represented at the World Health Organisation’s first global conference on air pollution and climate change. Governments, doctors and allied health professionals, inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations discussed how to measure pollutants, their sources and, critically, how to cut them.

Headline news from the conference was that the WHO committed to reducing global deaths from air pollution two-thirds by 2030, a welcome and lofty ambition. In addition, the WHO called for an Air Quality Convention to drive action for cleaner air.

Whether another multilateral agreement is needed will doubtless generate much discussion. There are many ideas on the table for how to cut air pollution. But most effective is the combination of legal measures, such as clean air acts or congestion charging, with the political commitment to drive change. For example, the UK’s Health Alliance on Climate Change (UKHACC) called for a shake-up in national air quality legislation on the eve of the WHO conference.

Air pollution is particularly a problem in a number of Asia-Pacific countries, a region which accounts for one-third of global air pollution deaths. A timely solution package was presented, including twenty five cost-effective measures that could contribute to achieving the World Health Organization’s Air Quality Guidelines and the Sustainable Development Goals.

This kind of scientific and technical evidence is essential to underpin societal and political action, but the WHO and UN teams also invited a diversity of participants, from Government Ministers to local active mobility groups, to emphasize the synergies and opportunities for collaboration around air quality, health and climate change. The sense of energy and momentum was powerful. Not all conferences have the bicycle mayors on hand to liven up proceedings; inspired by the São Paulo Bicycle Mayor’s entrance on a bike into the conference room, WHO’s Director General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus followed suit, cycling into the closing session of the conference. This was a great reminder of the health, air quality and climate benefits of getting around in more active ways.

Over the three days there were many alarming pictures of pink healthy lungs turned black through inhalation of air pollution, and uncomfortable statistics about the increase in deaths and disease. It was particularlydisturbing to learn that some western nations are consciously exporting more polluting products to low and middle income countries because they can’t be sold at home. Swiss traders, for example, were reported to blend the poorest possible diesel quality for African countries who had weak controls over sulphur content.

There’s some basis then for the WHO labelling air pollution as the new tobacco. The issue has become a toxic mix of deadly health risks combined with corporate self-interest and government inaction. One big difference, though, is that people choose to smoke whereas we cannot choose not to breathe.

Globally, more than 9 in 10 children are breathing air that is dangerous to health, the result, as climate champion, Christiana Figueres pointedly observed, of treating our atmosphere as an open sewer.

The sources of pollution that affect local air quality also affect global climate change. One of the striking points made in the recent IPCC 1.5 degree report is that the health co-benefits from cleaner air of actions to limit climate change could outweigh the cost of reducing carbon emissions in most major emitting countries. There are no more excuses! As the conference observed, the time for action is yesterday. The health community has a key role to play in addressing climate change, and taking on air pollution is a critical starting point.

As part of this response Unmask My City held a live stream event at the conference with Dr Fiona Godlee, Editor in Chief of the British Medical Journal interviewing three of the conference’s expert speakers: Dr. Arvind Kumar, Founder Trustee of the Lung Care Foundation, India; Dr. Maria Neira, WHO Director of Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health; and JP Amaral, Founder of Bike Anjo and São Paulo Bicycle Mayor.

As part of this response Unmask My City held a live stream event at the conference with Dr Fiona Godlee, Editor in Chief of the British Medical Journal interviewing three of the conference’s expert speakers: Dr. Arvind Kumar, Founder Trustee of the Lung Care Foundation, India; Dr. Maria Neira, WHO Director of Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health; and JP Amaral, Founder of Bike Anjo and São Paulo Bicycle Mayor.

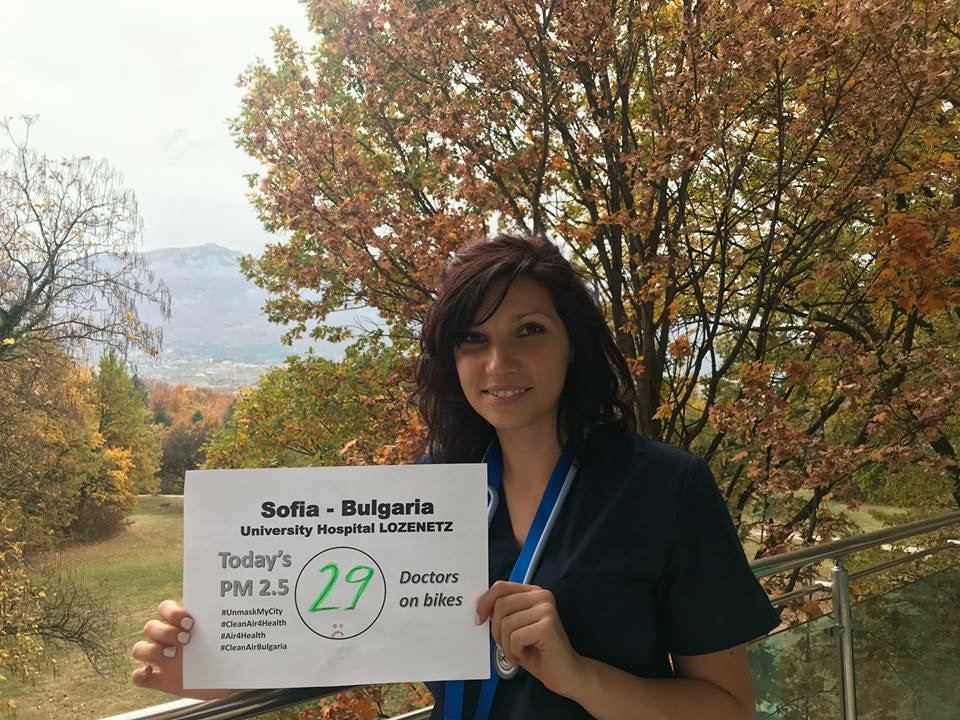

Importantly, UMC partners from Sofia, Seattle and London sent in photos of their air quality readings. These cards so caught the attention of conference attendees that they joined in creating a photo gallery of readings from Mongolia, Kathmandu, Bangkok, Geneva, Jakarta, Singapore and more to share with delegates.

Air pollution and climate change have no boundaries and people living around the globe have a lot to lose if we fail to cut emissions. And yet, if six continents tackle air quality and climate change, we will improve the lives and livelihoods of the over seven billion people on the planet, and protect the environment on which we all depend.